Hi everyone! My name is Maria, and I am an emerging environmental leader’s intern at Columbia Springs. I recently graduated from the University of Portland, where I studied Environmental Ethics & Policy and Philosophy. Over the past couple of months, I have been working with the education team here at Columbia Springs, helping with the field trip programs and family nature days. Through this internship, I have learned more about environmental non-profit and education work and am grateful for the opportunity to continue exploring professional pathways by shadowing and working with community partners. In my free time, I enjoy reading, listening to records, hiking, and trying new bakeries/ cafes around Portland. Read below to learn a bit more on a topic I am passionate about!

Where the Columbia meets the Pacific

I recently took a trip up to Astoria and spent a couple of days exploring the mouth of the Columbia River. I have seen the Columbia River from a variety of perspectives, from Kelley Point Park all the way to Kennewick, but this was my first time seeing where the Columbia meets the ocean. Just west of Astoria is where the largest river on the West Coast meets the largest ocean in the world, and it might just be my new favorite spot on the river.

Whenever I am driving along the gorge, as I make my long road trips home to North Dakota, I am in awe watching the rainforest climate shift to a drier climate around the Dalles; watching the landscape change from mountains and forests, to rolling hills and open fields. And all along the way, I have fun spotting slabs of Basalt Rock from the Missoula floods carved out along the roads.

Water enters the Columbia basin at infinite points along its pathway, whether it pours down as rainwater, or flows in from other rivers and streams. At Kelley Point Park, you can see where the Willamette flows into the Columbia, and here at Columbia Springs, we see how the spring water flows down the hills, and trickles into the river. Yet, I’ve never seen where all this water goes. When I continued the journey of the river, this time, the other way (to the west) I saw another story of the river. I saw how it ends; how it transforms.

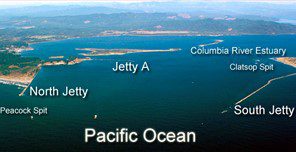

I spent one day hiking around Cape Disappointment on the Washington side of the river, and the other day exploring Fort Stevenson on the Oregon side. Both the North and South sides of the estuary have long extended Jetties, which are built of rocks and rubble to protect the shoreline from strong ocean tides and storm waves. The Jetties make maintenance of the channel easier and ultimately assist ships as they navigate to enter and exit the dangerous river channel. There are three Jetties along the estuary of the river, the longest one stretches 6.6 miles out into the estuary.

Another reason for these jetties is to help control the flow of sediment, along the mouth of the river. When the Columbia meets the Pacific, the river deposits sediment into the ocean, creating a sandbar and causing a stretch of shallow water, called Columbia Bar. This sandbar is everchanging with the flow of the two water systems. Its unpredictability, along with the intense waves of the Pacific, makes traversing the path from the river to the ocean even more challenging.

The mouth of the Columbia River has been nicknamed “the graveyard of the Pacific” due to its history of shipwrecks. More than 2,000 vessels have sunk in this dangerous meeting of waters. The remnants of one shipwreck, the wreck of Peter Iredale, are visible along the beach at Fort Stevenson.

On my trip, I was determined to find the best view of where the Columbia mixes into the Pacific – but this was incredibly difficult to do. The whole time I found myself unable to tell where the river ended and where the ocean began.

At one point, walking along the Columbia side of Fort Stevenson, I noticed the air getting heavier with the smell of salt, and more and more seaweed began washing up along the shore where I was walking. I wondered about the water, how salty was it here? What kind of fish can live in this specific salinity of water – water that’s not completely salt water, but not quite freshwater either?

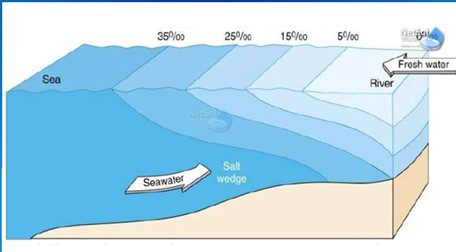

When freshwater initially begins to mix with salt water at the mouth of a river, the salt water tends to hang out at lower depths, because it has a higher density, while the freshwater hangs out closer to the surface. Because of this, a layer of freshwater gets pulled out into the ocean, at the surface, while a deeper layer of saltwater gets pulled slightly upstream. The two eventually mix, creating a hybrid salt-freshwater mix called “brackish water”.

This whole trip I spent trying to follow the water, to see where it goes, and how it changes into that final form. I got to see where a river stopped being a river and became the ocean, where the ocean greets and merges with the river. For a moment, you can’t tell river from ocean, it’s neither and it’s both at the same time. This water blurs the lines of identity and reminds me of the power of change that exists all along the river, all along the water cycle, and every other place in nature.

How are we connected to the ocean?

Just like Maria, the chum salmon raised at the Vancouver Trout Hatchery are intent on following the flow of the river as they migrate out to sea as babies and back home as adults. In fact, did you know that chum salmon are called five-day wonders? This is because hatch they swim headfirst all the way to their estuary in just 5 days after hatching out of the gravel. Coho, for comparison, will stay in the stream for a year before heading out and gently let the current take them as their heads point upstream. How cool is that?!

If tiny chum salmon can travel all the way to the ocean in just five days, what do you think that can we accomplish in the same amount of time? Help us continue to inspire wonder this season of giving by donating in support of Columbia Springs’ programming! From December 18th-22nd, donate online at www.columbiasprings.org/5days and help us reach our goal of $5,000 in 5 days. The person who donates the greatest number of times between these two dates will win a private Columbia Springs hatchery tour, featuring our baby chum salmon!

Each day from December 18th-22nd, we’ll be sharing fun chum salmon facts on our e-newsletter and social media accounts. Join our mailing list at www.columbiasprings.org/join-newsletter to make sure you don’t miss out! Questions? Contact us at events@columbiasprings.org.